BY BRITTANY PREOCANIN

When I came across an article arguing that the dashiki featured on Elle Canada’s twitter page was cultural appropriation, it made me instantly think of the blue dragon kimono that hung in my closet.

Ironically, my mother purchased it in San Francisco, with a tag stitched on the collar that reads “made in Vietnam.”

But is wearing a kimono, detailed with an embroidered dragon and Chinese script, a form of cultural appropriation?

Or, as journalist Jenni Avins from Quartz magazine, a Native American news site, suggests is it simply a form of borrowing?

“We have to stop guarding cultures and subcultures in efforts to preserve them… The exchange of ideas, styles and traditions is one of the tenets and joys of a modern, multicultural society,” said Avins.

It seems that there is a fine line however between what is considered borrowing or inspirational and what is downright demeaning and offensive.

“I feel like it’s all about the intention. If someone is creating a piece in fashion with the intent of discrediting or completely disregarding the historical or cultural values associated with it — that’s not inspiration,” said Fatma Othman, public relations student at Humber College.

For big name designers, inspiration from different cultures has existed for decades. Paul Poiret’s harem inspired trousers were designed in the 1910s and within the past two years, returned to retail stores throughout North America, with little to no backlash.

Interestingly enough, the history behind the harem pant comes from India, where it is known as a dhoti. Worn originally by men and later by women from middle-eastern tribes, the dhoti was used to represent modesty.

What’s concerning is how some forms of fashion, like the dashiki, are considered culturally offensive, while others, like the harem pant are not.

What Avins suggests is this idea of “cultural appropriation done right.”

She uses designer Oskar Metsavaht, founder of fashion label Osklen, as an example of how cultural appropriation doesn’t have to be a bad thing.

Metsavaht was inspired by the Amazonian tribe, Ashaninka and their culture. He used this inspiration and experience to create his designs in such a way that would not be deemed offensive. In other terms, they were not exact copies.

“I feel there is a fine line between copying and inspiration,” said Josette Cacnio, a Hamilton designer.

“If you’re going to copy something or use something as inspiration you should make sure you are taking that idea and elevating it to the next level, in a way creating something new from it.”

The headdress worn by Karlie Kloss at a Victoria’s Secret fashion show in 2012 was not recreated from an inspiration, it was a blatant use of a sacred garment as an accessory.

(Photo from dailymail.co.uk)

Aboriginal peoples who showed courageous acts of bravery and achievement for their tribe earned the honour to wear this war bonnet, and with all to respect, it should stay that way.

“A lot of companies and designers more so create certain products for the shock factor, just to get above in the industry,” said Christopher Lawrence, English student at Brock University.

Victoria’s Secret always has extreme, over the top accessories, like their signature angel wings, which is why the headdress probably seemed like a good idea at the time.

What needs to be uncovered and shared through the use of cultural inspirations however is the history behind these garments.

Metsavaht took part in a video posted on Quartz and borrowed ideas from the Ashaninka tribe in a way that provided the fashion industry with knowledge about the people and culture.

It’s as though the language and education designers showcase limits the amount they can be labelled offensive or culturally wrong.

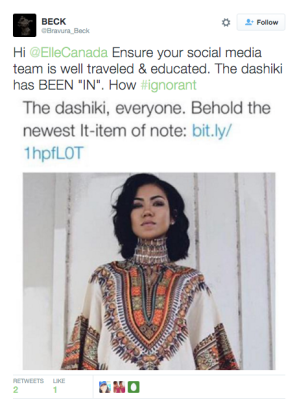

In the example of the Dashiki, followers became outraged on twitter over the fact that it was tweeted out as the “newest it-item of note” and because it was labelled outright as a dashiki.

One follower said, “Ensure your social media team is well travelled and educated.”

What was learned from the backlash is that the dashiki originally came to North America in the 60’s when black pride and counterculture movements were being embraced. In 2015, it was not necessarily “the new it-item,” but it also wasn’t being exploited.

It was simply being reintroduced to the fashion industry.

The dashiki is popular in Africa as a brightly coloured tunic with detailed embroidery that is worn by both sexes, with no ceremonial or sacred significance.

Delving into the history of my own Japanese inspired kimono, I found that the kimono, a common item of clothing, would be layered for warmth and came in many colours to represent social class.

Finding myself comforted by the silk material and soothing blue hues should not deem me disrespectful to Japanese culture.

When it comes to recreating in the fashion world, execution means everything, and in the case of cultural appropriation, the only way to do it right, is to explain your inspiration.

When I put on my kimono, I feel a sense of self, knowing that when I wear it I am not being insulting.

I am sharing a culture from the other side of the world.

MORE RELATED TO THIS: