STORY BY NICHOLAS OLSEN

PHOTOS COURTESY OF GEOFFREY GUNN, TIFF

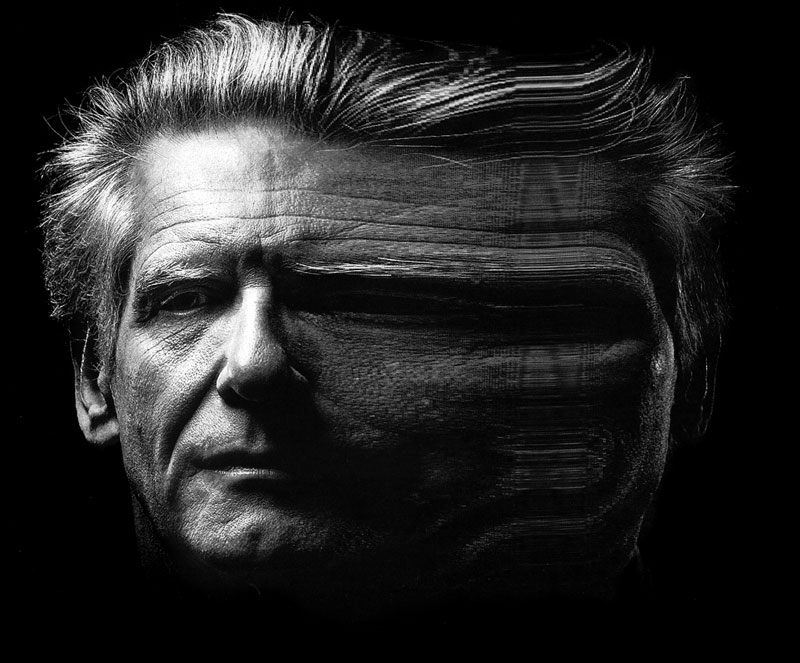

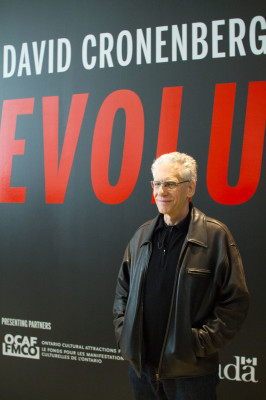

Provocative, horrific, audacious, Freudian and most importantly, Canadian. These are just a few words used to describe the legendary David Cronenberg.

Becoming a prominent filmmaker in the 1980s with notorious body-horror films such as The Fly and Videodrome, he ushered in a new era of horror, giving the genre an intellectual twist.

During the past year, a small group of administrators, faculty and alumni from the Faculty of Animation, Arts and Design at Sheridan has helped create a virtual timeline of Cronenberg’s career.

The timeline is part of a virtual exhibition which acts as an online companion to the Toronto International Film Festival’s major exhibit, David Cronenberg: Evolution, located at the TIFF Bell Lightbox in Toronto.

The virtual exhibition is the next step in TIFF’s Higher Learning Digital Resource Hub and will be available online in the near future.

Curators Piers Handling and Noah Cowan made an effort to seek out academic partners when designing the project.

“TIFF decided very early on in the application process to get the funding for the exhibition and the virtual museum, that it would work with academic partners. York, OCAD University and Sheridan were all part of the virtual museum,” said Angela Stukator, associate dean of Animation and Game Design at Sheridan.

“I was one of the coordinators. I worked very closely with the designer and the programmer. The designer was an alumnus from Sheridan named Matt Wiechec.”

Stukator and her team worked with TIFF reviewing 3D models, films and photographs. What they found was a complex vision.

They finally decided on a main theme for their project: mutation.

“We wanted something that created a sense of cells mutating into other cells. That idea evolved into the three sections and a vertical scroll as opposed to a horizontal scroll. So things evolve and develop as you trace down the timeline,” said Stukator.

The timeline is interactive, summarizing how Cronenberg’s movies have evolved over the years.

It proved to be a fruitful task for lead designer Wiechec.

“It was a really fun project for everybody involved. It was interesting because I didn’t know much about David Cronenberg before starting this, only a few of his feature films,” Wiechec said. “It was an honour to be creating something so visually rich, at least from my perspective as a designer. There is so much visual language inside Cronenberg’s work. He has so much interesting stuff to work from.”

Similar to the online counterpart, the major exhibition is organized into three sections, providing a loose chronological overview of Cronenberg’s career.

“Our guiding principle in displaying his work in this exhibition is to show this evolution, and we’ve done so by identifying three distinct chapters in his work that serve to structure many of our activities, and this chronicles Cronenebrg’s thoughts on humanity’s ongoing struggles,” said Handling, director and chief executive officer of TIFF.

The first section, Who is my creator?, delves into the director’s beginnings, from his early short films to his major breakthrough, Videodrome.

The first section, Who is my creator?, delves into the director’s beginnings, from his early short films to his major breakthrough, Videodrome.

This era sees his protagonists searching for father figures and meaning as they discover terrifying evolutionary possibilities.

In Videodrome, we see main character Max Renn (played by James Woods), a small-time television producer, looking for provocative content to gain viewership for his network. He discovers a satellite signal featuring sadistic and masochistic content.

When Renn seeks out the people behind this signal, he discovers something much more sinister, a mind control conspiracy that leads to the death of anyone unfortunate enough to view the show.

Featuring disturbing scenes of body-horror and virology, Videodrome is at first glance a basic horror film with extraordinary special effects, however, like much of Cronenberg’s work from this era, it has a deep philosophical and sociopolitical message.

His obsession with how modern technology shapes our body and mind is prominent in these early pictures.

Walking through this segment of the museum, a life-sized “flesh TV” from the film is shown.

Concept art and props are framed along the walls; pieces of life sized grotesque monsters surround guests.

Costumes are in the foreground. Scenes from feature films are shown all along the museum, complimenting the appropriate era.

Moving on trough the Cronenbergian evolutionary process, we are asked another question: Who Am I?

From Videodrome to eXistenZ, viewers now examine how his characters extend from their evolutionary experiments to experimenting on themselves, often using their bodies as a tool or vessel in their search for meaning, using science, technology, drugs and sex.

Perhaps his most famous film, The Fly, is on centre stage.

A teleportation pod used in the movie is big enough to crawl into and is surrounded by disturbing artifacts and imagery, including a life-sized statue of the fly monster and a severed ear.

This ear, of course, belongs to protagonist Seth Brundle.

Brundle discovers a revolutionary way to teleport humans, but makes a fatal mistake by using himself as a test subject.

His DNA accidentally becomes fused with a fly while using the teleportation device.

The outcome? His slow and terrifying transformation into a human-sized fly creature.

Guests can take a look at how Cronenberg designed this transformation via early concept art/notes from the production.

Nearing the end of the exhibit, a final question is asked: Who are we?

Beginning with Spider (2002) and coming up to his latest film, Cosmopolis, this final section shows the director’s protagonists move beyond their private odysseys and into the social world.

Cronenberg begins to break out of the crude, unpolished look of his early movies, entering a more sophisticated realm.

Artifacts and rare footage from A History of Violence and Eastern Promises dominate this section.

These later works still hold the explicit violence and psychological terror, but are wrapped in a big budget package.

“I don’t think there is that much difference between his early films and his later films, I think they are just more sophisticated. If you look at a film like A History of Violence or Crash (1996), there is a lot of violence in it too. But the psychosexual themes are consistent throughout his films,” said Stukator.

Cronenberg touches on familiar themes, such as the divided self and how the inherent violent nature of human kind masks itself in everyday life.

His signature sociopolitical allegories also remain. His latest feature, Cosmopolis shows a young billionaire with genius level intellect finding it hard to navigate through a timid existence.

The rich young man is shown roaming the city in a highly-armoured limousine, while conversing with equally brilliant minds about the inseparable connection between technology and capital.

Outside the limousine, society has crumbled. The poor riot in the streets, undoubtedly the director’s own little commentary on the Occupy movement.

Themes from his genesis remain the same, but Cronenberg continues to evolve, asking equally challenging and provocative questions.

“He fundamentally challenges this notion of a utopian future where both man and society are in some way perfectable,” said Handling.

“There may well be a human desire for progress and a desire to improve man/woman and society, but his work acts to question these assumptions. The great project of western civilization is held up under a magnifying glass in his hands.”

The exhibition will run at TIFF’s Bell Lightbox until Jan. 19. The virtual exhibit can be viewed on the fourth floor of the building and will be available online soon.

Learn more about TIFF’s Higher Learning Digital Resource Hub, visit tiff.net/higherlearning.