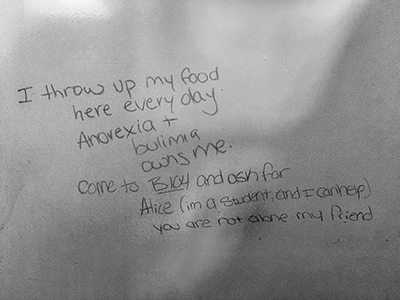

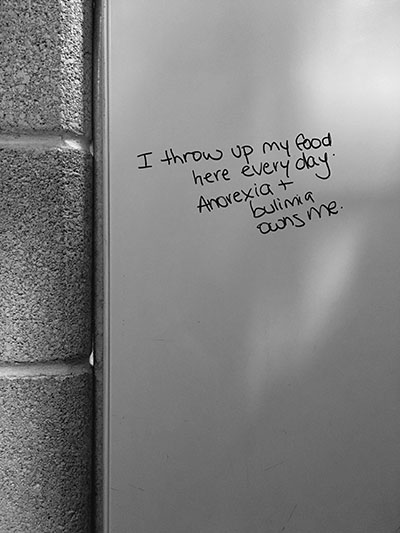

Writing on the Wall

Last month inside a women’s washroom in the SCAET building a message was written on the inside of a stall. The next day there was a response. Later in the day the stall was cleaned. (Photo by Erin Queenan/The Sheridan Sun)

BY ERIN QUEENAN

“I throw up my food here every day. Anorexia and bulimia owns me.”

On Oct. 5 a student wrote this on the inside of a bathroom stall, neatly and with black marker in the SCAET wing at Sheridan College. Dark and prominent, its message was hard to ignore. The next day, whether intended or not, the message generated a response. “Come to B104 and ask for Alice (I’m a student and I can help.) You are not alone my friend.” A couple hours later it was all washed away.

Eating disorders: anorexia, bulimia and binge eating are serious mental health disorders that can greatly affect someone’s physical health, relationships and quality of life. While it is difficult to put an exact number on who is affected in Canada, the National Initiative for Eating Disorders estimates 150,000 to 600,000 people.

Early detection and treatment are the best solutions, according to Suzyo Suman Bavi, a counsellor in Student Services, room B104. Before working at the college, Bavi cared for inpatient eating disorder patients at Cambridge Memorial hospital. There he saw first-hand what the mental illness could do if left untreated for years.

The disease destroys all parts of the body. Severe loss of muscle and fat is easy to observe but more critical problems lie below the surface. When the body does not receive adequate nutrition and energy the heart will drop to an abnormally slow rate (40-30 BPM) and low blood pressure to conserve energy. Teens with anorexia could have the bone density of an elderly person as well as muscle weakness, dehydration, fatigue and severe nutrient deficiencies.

Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness, according to a study by Patrick Sullivan 2002, it is estimated one in ten individuals diagnosed with anorexia will die within ten years of the onset of the disorder if not treated. However this number could be more according to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. Mortality rates reported on those who suffer from eating disorders vary as those who do die from the disorder ultimately die of heart failure, organ failure, malnutrition or suicide. The medical complications of death are reported instead of the eating disorder that compromised a person’s health so it is difficult to record.

Most mental health problems start in the teenage and young adult years. In treating these illnesses early detection is crucial. This is what attracted Bavi to become a counsellor at Sheridan. “I wanted to be in the front end and be able to help in the early stages when someone is just beginning to develop a mental health disorder. It is much easier to maintain and manage it if issues are detected early.”

Lia Nardone, a Broadcast Journalism 2015 graduate, won an award last year for best documentary in her class for her video called “Less than One Hundred” which chronicles Nardone’s intimate struggles with an eating disorder.

Nardone, 23 years-old, says she remembers since she was young wanting to be in control of things. If structured routines were disturbed she would feel intense anxiety. In third grade she began not liking the feeling of eating in front of people so she remembers deciding to go home for lunch. She wondered what it was about eating that made her feel that way and realized it wasn’t so much about the food as it was about people observing what she put into her body. It was with that awareness she started to diet later in adolescence. For Nardone it was about monitoring how people perceived her. “I liked people seeing me the way I wanted them to see me.”

The exact cause of an eating disorder is unknown. The science is not there yet. According to the Mayo Clinic, it is thought to be possibly genetic predisposition, triggered by other psychological or emotional problems such as low-self esteem and perfectionism. In addition, North American society and media put an immense amount of value on being thin. In contrast, Bavi, who is originally from Zambia, says some places in Africa have never seen one person with an eating disorder.

Looking back, Nardone can see the red flags in childhood, however, it was only around the age of 20 that realized she had eating disorder symptoms. What had begun as dieting, grew to eating less and less, and exercising compulsively, to abusing laxatives and then, finally, not eating at all. “It became a problem when I would feel very guilty if I ate anything. I was very distant. People worried about me. It was more than just a phase and I knew there was something not right about it.”

At this point Nardone was showing symptoms of both anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Anorexia nervosa could be defined as an intense drive for thinness, a refusal to maintain a minimum weight, denial of hunger, rigid rituals around food, obsession with dieting and withdrawal from relationships. Bulimics are different in that they can eat a lot, however they’ll rid themselves of calories by either forcing themselves to vomit, abuse laxatives or excessively exercise.

The third disorder, binge eating, can often develop after someone has been anorexic for some time. Instead of denying themselves food they will swing to the other side and eat huge volumes in secret, graze without feeling satisfied and often exercise excessively to compensate. This person usually is overweight, though not always.

There is a fourth condition, known by some as “orthorexia,” but it is not recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. “Orthorexia” is characterized as a fixation on righteous, pure, “healthy” eating. Although it is unrecognized, a growing number of patients, including Nardone, are associating with it.

A lot of Nardone’s recovery was on her own. She got counselling at Sheridan, which encouraged her to practise cognitive behaviour therapy by writing down and analyzing her thoughts and what made her feel anxious and depressed. She was in her first year of broadcasting when she felt like she could take these steps. She felt she was in the right place and program and was supported by friends, even if they didn’t know her internal struggle. Once she did open up about it, though, right before the documentary was made in the first semester of her second year, she recalls it as an “emotional and healing thing.”

The stall on Oct 5. The next day a student named “Alice” replied. (Photo by Erin Queenan/The Sheridan Sun)

Bavi says one-on-one counselling is crucial in recovery because one of the aspects of an eating disorder is distortion. He says the best form of treatment is done by a multidisciplinary team: a counsellor, nutritionist, psychiatrist and physician. When students at Sheridan having eating disorder symptoms, counsellors will always recommend they see the Health Services at Sheridan to get a requisition to go to an outpatient clinic such as Halton Health Care Services, Trillium Health Care Services at Credit Valley Hospital or Danielle’s Place in Burlington.

In Bavi’s opinion the girl that wrote on the bathroom stall is reaching out and he wants her to know that he can help. “We have a very good team here at Sheridan. She can call me anytime Monday to Friday. She has to be assured that whatever is discussed, within the student is strictly confidential. The sooner she comes, the better chance we have at helping her. People do get better.” Counselling is available at the Student Services Centre, B104 from 9am – 5pm Monday to Friday. Students can call in to book an appointment or drop by.

Hearing about the girl at Sheridan saddens Nardone. “I would want to give them a hug. I know it’s controlling, you base everything off of it, but there’s so much more to you. Your instinct as a human being is to survive and your brain is telling you not to. You have to start thinking differently to recover. You have to be open.”